by Ursula Kampmann

September 8, 2011 – Amphipolis and Philippi are the destinations of issue no. 10. They were once incredibly rich cities whose citizens earned their living with the trade of gold, silver and building timber …

Day 26, July 6, 2011, Amphipolis and Philippi

We stayed for another day in our quarters near Kavala to visit the archaeological excavations located nearby, Amphipolis and Philippi.

The Lion Monument of Amphipolis. Photograph: KW.

The most photographed photo scene of Amphipolis is the big lion standing adjacent to the main road. Its fragments were discovered during the Balkan Wars in 1912/13 and put together again in 1936. The Lion Monument is connected with Laomedon, fleet general of Alexander, who was a native of Mytilene but held citizenship of Amphipolis nevertheless. He was one of the oldest friends of Alexander and accompanied him when he was exiled from the Macedonian court. After Alexander’s death Laomedon was given Syria which, however, he didn’t manage to hold. The only further detail known about him is that he joined outlawed Alketas.

View at the Museum of Amphipolis. Photograph: KW.

Only few tourists manage to get to the remarkable Museum of Amphipolis we associate quite peculiar memories with: when we visited Amphipolis in 2004, the museum already existed. At the box office we were dealt with rather carelessly because a local potentate entered to accompany ‘his’ tourists – two inconspicuous young people tiptoeing around the museum. While they looked at the attractions, our potentate was at a loose end.

View inside the Museum of Amphipolis. Photograph: KW.

Being bored, he wandered through the rooms, lit a cigarette, smoked with pleasure and then held the smoldering butt in the hand. There were no ashtrays. Well, what did he do? He stubbed out the cigarette on one of the statues and threw the butt in the corner. Usually the guards begin to call when someone walks contrary to the direction of the round tour (let alone when someone takes an illegal photograph including flashlight) but this they winked at. As a matter of fact, back then we swore never to return to Amphipolis again. This time, on the contrary, the polite guards made up for some things. Unbelievable, how the atmosphere in a museum depends on this most often underpaid and often unregarded people. The curator, on the other hand, is of no interest to the ordinary visitor.

Amphipolis. Tetradrachm, c. 369/8 B. C. Apollon. Rev. race torch. From auction Gorny & Mosch 190 (2010), 117.

But let’s get back to ancient Amphipolis. Its coins with the en-face portrait of Apollon is considered the pinnacle of the ancient art of die cutting. Plus, in antiquity Amphipolis ranged amongst the most important cities of Northern Greece. It became famous first under its characteristic name Ennea Hodoi (=Nine Ways). Hence it was situated at an important junction of streets where any number of strategians wanted to own a fortification.

Amphipolis. Obol, 420-357. Young man. Rev. fish. From auction Gorny & Mosch 186 (2010), 1224.

Already the Milesian tyrant Aristagoras wanted to establish his new headquarters here after he had fled from the Persians in 497. The Edones, however, wasn’t pleased with that at all and beat him to death. The Persian allegedly built a bridge in 480 and, as a sacrifice to the river god, buried alive nine young men and nine maidens. In 475, the Athenians arrived. They were more persistent. After some attempts had failed, finally, under Perikles, an Athenian colony was established near Ennea Hodoi. It was given the name Amphipolis and became a splendid starting point for the Athenians to exploit the surrounding region.

Demetrios Poliorketes. Tetradrachm, minted in Amphipolis, 289/7. From auction Gorny & Mosch 196 (2011), 1424.

In the Peloponnesian War, Amphipolis was fiercely fought over. After all, Athens got its supply of wood, required for armaments and for building ships, from here. This is why history owes one of their greatest works to this city. Historian Thukydides had failed in commanding the fleet to protect Amphipolis and hence was exiled which gave him a lot of time to write a certain book…

After the war was over, Amphipolis refused to be dominated by Athens again. It remained autonomous until Philipp incorporated the city into his empire. Until the end of the Macedonian Empire, Amphipolis was an important center which is also attested by the many coins of the Macedonian kings that were minted here. Amphipolis witnessed the assassination of Roxane and little Alexander IV as well as the victory celebration of Aemilius Paullus over Perseus. Archaeological sources tell of a bloom in early Byzantine times but at some point Thessaloniki became more and more important and hence displaced Amphipolis so that it turned into the ruin we know today.

Silver ossuarium with golden laurel wreath. Photograph: KW.

The Museum of Amphipolis has much to offer including some noteworthy sepulchral finds, like this silver ossuarium which is associated with the Spartan Brasidas for reasons being incomprehensible to the visitor but perhaps reasonable. That Brasidas had taken Amphipolis from the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War. He was so popular in the conquered city that he was celebrated as founder-hero after his death he had met when defending Amphipolis against the Athenians.

Necklace. Photograph: KW.

Only close inspection reveals the beauty of the jewellery.

Knot of Herakles. Photograph: KW.

Just look at this incredible knot of Herakles. That decorative shape got its name either from the way the hero had knotted the snakes after their attempt to kill him or from the way he wore his lion skin. Today, the knot is – rather boringly – called reef knot.

Tetradrachm from Amphipolis. Is it truly authentic? Photograph: KW.

Of course, there were coins present. Upstairs there were some showcases on display presenting the coinage of the surrounding Greek cities. In the main room a showcase displayed the coinage from Amphipolis. No, no coin was that good-looking that I was tempted to buy it. Thank goodness the plastic prevented a thorough inspection, which might have revealed that one or the other piece was a cast.

The excavation site high above the Strymon River, the sea in the background. Photograph: KW.

High above the city, behind a sports area and rather thanks to intuition than a signpost indicating the excavation, we found the site, guarded by a kind elderly man, who was accompanied by his grandson and his dog. He was truly excited at us coming, handed us a Greek leaflet into our hands and even apologized since he only had a Greek edition of it! Entrance fee, no, he didn’t want any.

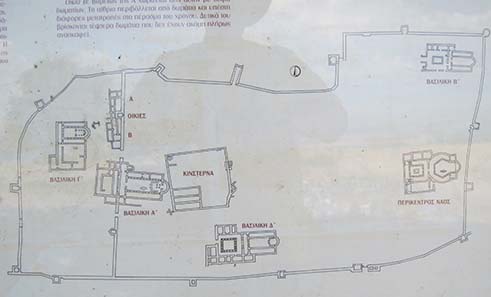

Map of the archaeological excavation of Amphipolis. Photograph: KW.

Hence we entered a huge excavation area where quite a number of Byzantine basilicas had been found.

Basilica A, B, C or D – I lost track. Photograph: KW.

There were four basilicas here and an early Christian central-plan building. Everything was splendidly explained and easily comprehensible with the guidebook in our hand (the Greek language didn’t annoy at all) but later, when looking at the pictures of the four basilicas, I realized that obviously they didn’t stick in my mind so much that I could tell them apart.

An apse built from column shafts. Photograph: KW.

I was more impressed by the resourcefulness of the architects and how they made good use of Classic columns when constructing a first-class early Christian apse.

Early Christian central-plan building. Photograph: KW.

It is easier to recognize this early Christian central-plan building. Its groundplan was unique. Despite the thrilling excavation site, we were getting more and more anxious. After all, the day before we had learned that Greek excavations close at 3 p. m. and we intended to drive to Philippi today, so we left the site in rather a hurry, got into the broiling car and headed for our next destination.

Krenides. AE, 360-356. Herakles. Rev. club and bow. From auction Gorny & Mosch 191 (2010), 1240.

At present-day Philipp there were a number of settlements located in antiquity because the area was renowned for its abundance in gold, silver and building timber. Known are Krenides and Daton, which was founded by Athenian exiles. Under the leadership of Kallistratos the city was founded in 360/59 B. C. and may well have produced the coins on which the settler call themselves Thasians on the mainland.

Philippi. Hemidrachm, 356-345. Head of Herakles. Rev. tripod. From auction Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 125.

In 356, the city was threatened by Thracians and asked Philipp II for assistance. He had fortifications built in the city and re-named it into Philippoi, after himself. There is not much we know of the city in Hellenistic times. At any rate, at some point the mines were depleted. Philippi’s main significance in Roman times was due to a station of the Via Egnatia being situated here.

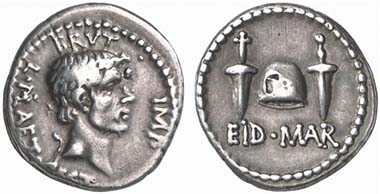

M. Iunius Brutus. Denarius, 42 B. C. Head of Brutus. Rev. pileus between two daggers. Cr. 508/3. From auction Künker 124 (2007), 8483.

That very location, at the Via Egnatio, made Philippi one of the decisive locations of world history (and Shakepeare’s “We will meet again at Philippi!” did its share to make it a location memorable embedded in the collective memory of mankind). It was here where the supporters of Marc Anthony and Octavian fought the assassinators of Cesar. We know the outcome of the story. Brutus and Cassius lost. Crassus committed suicide still in Philippi, Brutus did the same a little bit later.

Philippi. Bronze, 1st half of the 1st cent. A. D. Victoria. Rev. three standards. From auction Künker 124 (2007), 8705.

The victors subsequently founded a colony for some legionary veterans and gave it the name Colonia Victrix Philippensium. The city flourished so much that a humble itinerant preacher called Paulus went to Philippi to found the first Christian community on European territory. As indicated by his letter to the Philippians, however, with an exhortation to live together peacefully, he wasn’t always pleased with it.

By the way, Philippi owes to Paul its standing as center for pilgrimage in Byzantine times. This is why the city was rebuilt every time it was destroyed over the course of the Migration Period. As late as the 14th century, after the Turks had conquered the city, it finally deserted.

The Theater of Philippi. Photograph: KW.

We had driven like hell to arrive in Philippi in time. But there was really no need to do so: the excavation was open until the evening. Only the (new) museum was – as usual – closed at 3 p. m. That was close shave. Hence, we hurried to see the magnificent theater, which presumably is one of the most ancient buildings of Philippi and was commissioned by Philipp.

The showcase for coins in the Philippi Museum. Photograph: KW.

We reached the museum just in time – it was air-conditioned and that was a real pleasure in the heat. Directly at the entrance we were welcomed by a showcase with coins to which even magnifications were added. But they weren’t the only “numismatic” objects.

Earring in the shape of a Macedonian shield. Photograph: KW.

Here you can see an earring in the shape of a typical Macedonian shield.

Weight for the market place. Photograph: KW.

And this is a weight which represents an empress, either Eudokia or Pulcheria.

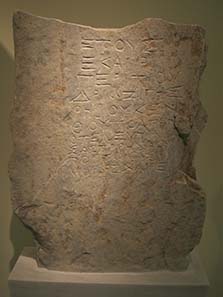

Gravestone for a killed participant in the Battle of Philippi. Photograph: KW.

That, however, weren’t the only attractions. Here you can see a gravestone, dating to 43/42, for a Thracian who fought on the side of Rheskuporis. The latter is known to have supported Brutus and Cassius.

Portable sun-dial. Photograph: KW.

And this peculiar object is a wrist watch from ancient times, a portable sun-dial whose remains were unearthed in Philippi.

The dungeon of Paulus. Photograph: KW.

Close by the museum a small room is situated which is – historically incorrect – associated with a capture of Paul of whom the Acts of the Apostles tell the following: “But when her masters saw that their hope of profit was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the market place before the authorities, and when they had brought them to the chief magistrates, they said, ‘These men are throwing our city into confusion, being Jews, and are proclaiming customs which it is not lawful for us to accept or to observe, being Romans.’ The crowd rose up together against them, and the chief magistrates tore their robes off them and proceeded to order them to be beaten with rods. When they had struck them with many blows, they threw them into prison, commanding the jailer to guard them securely; and he, having received such a command, threw them into the inner prison and fastened their feet in the stocks. But about midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns of praise to God, and the prisoners were listening to them; and suddenly there came a great earthquake, so that the foundations of the prison house were shaken; and immediately all the doors were opened and everyone’s chains were unfastened.”

Basilica B. Photograph: KW.

Its importance as pilgrimage destination Philippi owes to its most impressive ruin which amazed travelers already in the 19th century. The three-isled basilica with the (today missing) central cupola was built around 550 following the Hagia Sophia.

Agora. Photograph: KW.

It is situated in an excavation area, separated by a street, behind a huge square where once the agora with the public buildings was.

Carving in stone. Photograph: KW.

Anyone paying attention comes upon interesting details like this carving of an eagle. We, however, lacked attention by then. It was hot. We were tired. Compared to what we had seen in Thrace, this excavation was rather crowded. Outside, a beer in the shade tempted. Thus we decided to drive home to recover. After all, we had a busy day ahead. We needed to go South, destination Patras, where in a few days time our ferry would depart.

Join us for our next issue when we are going home and accompany us on our visit to come cities that had made history: Pella, Thebes and Delphi.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.