The interview was conducted by Ursula Kampmann

Translation: honeycutshome

October 30, 2014 – In 2009, Bernd Kluge, Director of the Münzkabinett (Coin Cabinet) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, gave Ursula Kampmann an interview and explained to her what it meant to work in the Münzkabinett in the GDR era and to lead it through the Turnaround and the German Reunification. On the occasion of his retirement on 1 October, 2014, we publish this interview again in CoinsWeekly.

UK: Hence, it must have been a massive change for you when the Turnaround happened.

Staff of the Münzkabinet janting in 2008 (from right to left: Elke Bannicke, Norbert Kneidel, Gisela Stutzbach, Ingrid Feist, Bernd Kluge, Viola Gürke, Regina Boreck, Wolfgang Steguweit, Bernhard Weisser. Photo: private.

BK: Well, this whole Turnaround, i.e. the months between October 1989 until October 1990, was a time you can hardly understand in retrospect. So much changed in so little time, incredible! In the East, the first thing that happened was that all structures were crushed. Thus, directors-general and party minions suddenly stopped to be important. Let’s vote them out, best to put them up against the wall. That was how it all started. Grassroots democracy. Then, researchers’ councils were established and councils of conservators, all sorts of professions organized in councils and intended to rule the museums. This time of grassroots democracy was quite lively, but it also led to some dislocations. I wasn’t that involved. It quickly turned into a forum for people who generally sat in the backyard and weren’t really known for their drive but who suddenly sniffed their chance to get even with the old elites. Besides, at that time I had my hands full both with my book (Deutsche Münzgeschichte von der späten Karolingerzeit bis zum Ende der Salier [ca. 900 bis 1125], Sigmaringen 1991. Author’s note) and the preparations of the great exhibition on the Salians in Speyer in 1991.

UK: Straight to the point: do you recall your first day at work after the Fall of the Wall?

BK: Sure I do. The first day at work after the wall had fallen was a Friday. Steguweit and I were on duty as is befitting Prussian civil servants – although we actually weren’t civil servants by then. All the other personnel of the Münzkabinett showed up at work, too. I had heard the famous speech of Schabowski on the radio the night before but I didn’t understand it in the way that all barriers were open as of then. So, on 9 November, I didn’t dash off and took the Bornholmer Brücke to enter the West. In addition, we had a guest staying with us, a friend of my wife from the Brandenburg hinterland, who was about to go on her very first, officially permitted, trip to the West the next day, to visit her relatives. We had to calm her down, with all the commotion. The next morning, everything was clear, yes, the wall is open. And of course we went to the Friedrichstraße to have a look for ourselves. As a matter of fact, there wasn’t so much going on there. We crossed the barrier as late as Saturday and went into the West to experience the new world first-hand. Besides, you needed to have special documents when you wanted to cross the border with children under 14 – at that time, we had three, all of them under 14 – and these documents we could only get after hours of queueing up at the Volkspolizei (People’s Police). We certainly didn’t want to leave our children behind. I mean, it was a madhouse.

UK: How did things develop at the museum?

BK: The motto was grassroots democracy after the collapse of the SED dictatorship. Much frustration erupted that had been bottled up, and injustice, too. For example, the museum staff voted on the continuance of the Director General of the East Berlin State Museums, Günther Schade. I voted, too, and I voted for his continuance in office. That was the position of more than 50%, and so Günther Schade continued to serve as Director General and he did a good job in the unification of East and West. After the Reunification he became the deputy of the Director General, just like most of the other East directors who took second billing to their colleagues from the West. Civil service law! Who knows what might have happened if we had unelected Günther Schade. He remained in office while others left voluntarily. The party secretary, for example, was never seen again. She simply disappeared.

UK: What happened next? After all, the East Berlin State Museums were put under the control of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

BK: Indeed, after the grassroots democracy period, the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz took command. On 3 October, 1990, we became part of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz. A big meeting of the East staff had been summoned during which the Foundation’s President, Werner Knopp, the Director General, Wolf-Dieter Dube, and the personnel manager turned up to inform us that we had become members of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz. I liked that, I always wanted to see that Prussian element incorporated into the name of the museums.

UK: There weren’t any problems? Was the East staff structure that easily adapted for the conditions of the West?

BK: That generated huge problems. In the first stage after the Reunification we spent all our time on writing lengthy job descriptions for each staff member with minute specifications of how much time it took which member to do what and when. The purpose was to find out the pay grade for every individual. That was an awful lot of work because we had to assess according to criteria we know almost nothing about. We tried our best. The results of our efforts were then sent to an examination board. I reckon it made the hair of the members of that board stand on end when they saw what the ‘Ostler’ had fabricated there in order to assure their personnel a livelihood.

UK: Were you happy with your new salary?

BK: For us researchers it was something like heaven. The peace of the museum niche in the GDR came with only a modest payment. For years, I had earned 800 mark, until the Turnaround it rose to more than 1,000 GDR mark, gross of course. That was more than two times my former salary, and in D mark at that. But there was much trouble going on amongst the workers – the museums had their own metal workers, carpenters, electricians, and painters. Back in the GDR, the worker used to be king and only paid half of the taxes of an employee. That changed, and all of a sudden the workers earned less money net. If every dirge was actually justified, I can’t say.

UK: In the days of the GDR many more people were working at the museum, compared to the West. Did you witness a large round of dismissals?

BK: No. According to the numbers in the West, the museums in East Berlin were overstaffed. But the jobs were there and the people that were doing these jobs couldn’t simply be sacked. A solution was found in that only very few positions were cut and ‘KW-Stellen’ were created. KW meant ‘kann wegfallen’ (‘can be cancelled’). It all happened in stages: KW 1995, KW 2000, KW upon retirement. All in all, people were treated rather humanely. Knopp and Dube have dealt with this aspect of the unification process very successfully as well, by and large. The Münzkabinett, on the other hand, had to pay the price. We had seven academic researchers at the time of the Turnaround. Today, the number has dropped to only four. That was the tribute to the unification.

UK: If you look at the daily routine back then and now, what differences do you notice?

The big reception at the Märkisches Museum on the occasion of the XIIth International Numismatic Congress held at Berlin in 1997. Photo: Reinhard Saczewski.

BK: It depends on which area you have in mind. Everyone from East Germany had made his own experiences, but, generally speaking, the experiences were far-reaching for all of us. When I drink a glass of wine or eat some cheese today, I still realize how wonderful some creature comforts can be which we knew almost nothing about, living in the GDR. Working in the GDR, on the other hand, almost seems like paradise, in retrospect. The jobs were stable and there was only little pressure to perform. Admittedly, the wages were not that big, either, but they were sufficient against the low rents and food prices, albeit both parents had to work to support a family of five. At the museum, you were left in peace, you could do research but you were not obliged to. It was not that nobody cared at all, but the focus was not so much on the actual output as it is today. And we had much more personnel. At present, the job that used to be done by two people has to be accomplished by only one employee. When I took over as director in 1992, my academic projects were put on hold for the time being. In turn, the Kabinett has improved its standing on other areas. Since 1993, I teach medieval numismatics at the Humboldt University Berlin. Once the Münzkabinett reappeared at the international scene there were more and more tasks to fulfil. Still under Steguweit’s aegis Berlin was appointed host of the 1997 XIIth International Numismatic Congress. It has taken a considerable amount of time to make all the necessary preparations for this congress, and for both the usual weighty ‘Survey of Numismatic Research’ accompanying it and the subsequent publication of the two congress volumes. But the congress had won us international reputation in turn. In 2000, Steguweit followed with organizing the XXVIIth Congress of the International Art Medal Federation FIDEM at Weimar. In addition, we have initiated two new series: Die Kunstmedaille in Deutschland (26 vols. so far), Berliner Numismatische Forschungen, Neue Folge (9 vols. so far), and Das Kabinett (11 vols. so far). And this is also the reason why no new Dannenberg has been published so far – which is sometimes held against me. At present, museums have to attract visitors. Dos, exhibitions, events have priority, at the dire cost of research and even of the academic work on the collection.

Building site with construction ladder. Access through the window only. Photo: Bernd Kluge.

UK: And then there was the great renovation. By the way, why wasn’t it already undertaken in the GDR era?

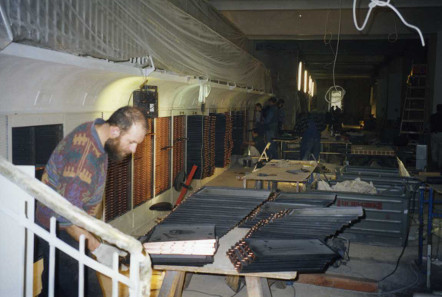

Restauration of the 14,500 lead drawers in the Great Treasure Vault in 2003. Foto: Bernd Kluge.

BK: If we had tried any more substantial renovation of the Münzkabinett, with the limited technical means and the material bottlenecks prevalent in the GDR, we only would have worsened the situation. So we accepted only the most essential measures and prevented any disimprovements. What we did was justified but, of course, everything was in a pretty bad state in 1990. The technical equipment of the restoration workshop was hazardous to health, for opening and closing the steel-reinforced doors and windows of the Great Treasure Vault special tricks and long experience were required, sanitary installations, lighting and electric plants stemmed from the 1950s. Individual measures started as early as 1990, and in 1998, the Bode Museum was closed completely and the general restoration began. The Münzkabinett has been rebuilt down to its foundation walls and reconstructed afterwards. That had cost us much time and effort and the tax payer 10 million D mark. To keep our collection protected against the construction works during the renovation of the Bode Museum and accessible for us was a major task alone! It meant that we had to move at regular intervals. Access was difficult. With offices and library we were stationed upstairs in the Pergamon Museum while the collection was downstairs in the Bode Museum. Going downstairs, going upstairs, and crossing the yard while holding the tray in hand. That was somewhat byzantine, time-consuming, and it also put the collection at risk. The anecdotes from this period of time are something for my memoirs.

Open days at the Treasure Vault. After the renovation, Wolfgang Steguweit gives a tour around the Treasure Vault of the Berlin Münzkabinett in 2004. Foto: Reinhard Saczewski.

UK: You could have opted for a more convenient temporary solution.

BK: Well, we wanted to invest all the money we were given for the building project in nothing else than the building project. If we had built a temporary accommodation we would have spent half of the money that was intended for the entire Münzkabinett. Hence, we made do with provisional arrangements. Admittedly, the collection has suffered a bit during these years. Take the copper and the bronze coins: today they display heavier traces of corrosion than during the reconstruction. At the moment we are busy cleansing the entire collection, from A to Z. The extent of the dust pollution alone is that big that, strictly speaking, we check tray after tray and, if necessary, even replace them.

UK: One concluding question: what do you think the future holds for the Berlin Münzkabinett?

BK: It is difficult to venture a prognosis. At present, numismatics is going downhill wherever you look. That goes not just for a Münzkabinett but for a university as well. It is the problem of the ‘small’ disciplines. Virtually no vacation of a retiring employee is filled in exactly the same way. The worse the situation in the minor institutes, the more important it is to at least have one or two institutions left in Germany in their old capacity as lighthouses, in order to prevent the fire from extinguishing. One such lighthouse is Berlin, certainly. I will do everything I can in the years to come in order to keep the status quo. If, however, the Münzkabinett will remain a museum in its own right, when I will be retiring in five years from now, is a question I cannot answer in the affirmative with full conviction. We watch smaller houses being merged, and one of these smaller houses definitely is the Münzkabinett.

But that time hasn’t come yet, we have the Prussian Civil Service Law and a director continues to be a director until he is retiring.

Part 1 of the interview you find here.

Part 2 of the interview you find here.