by Chris Rudd

First 42 gold staters from the Buckingham hoard, found 16-17 December 2006. “Ed was giggling like a schoolgirl” says Heritage.

Picture source: R. Tyrrell, Bucks County Museum/PAS.

Around midday on Saturday 16 December 2006 two metal detectorists strolled onto a field near Buckingham and within a few minutes picked up a valuable gold coin that was lying on the surface. By the end of the weekend 42 had been found. By 11 March this year a total of 70 iron age gold staters, mostly minted by the local Catuvellauni tribe over 2,000 years ago, had been harvested from this fertile field.

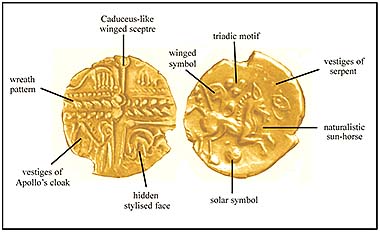

Most gold staters in the Buckingham hoard are early Whaddon Chase type, possibly minted by Cassivellaunus c.53-51 BC as tribute money.

Picture source: R. Tyrrell, Bucks County Museum/PAS.

A piece of good luck? Far from it. This significant gold hoard was recovered from the wet winter soil as a direct consequence of a piece of good planning and many weeks of meticulous metal detecting, responsibly conducted with the prior permission of the landowner and with the knowledge of local archaeologists, and fully reported at each stage to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS).

The gold team: Gordon Heritage (centre) with Edward and Andrew Clarkson. Motto: homework before fieldwork.

Picture source: G. Heritage.

From start to finish this was a team job. The team was two detecting brothers, Andrew and Edward Clarkson, led by Gordon Heritage, an experienced player in the treasure field who realises the value of working closely with archaeologists and the PAS. Heritage had previously studied an old book containing an old map. Looking closely at the map he calculated where some buried treasure might be waiting to be unearthed, identified the right site and went straight to it on his first visit. He used his head before he used his feet. He did his homework before doing any fieldwork, because he knew that good research brings good results.

Heritage and the Clarkson brothers have excavated 70 gold staters from their secret Buckingham site. 57 of these are early Whaddon Chase type staters (VA 1476) of the Catuvellauni of Hertfordshire, 11 are Atrebatic Uniface staters (VA 216) of the Atrebates and Regini of Surrey and Sussex, and two are Chute type staters (VA 1205) of the Durotriges of Wessex. All 70 of these gold coins were minted in the mid first century BC.

The hoard represents another success for Dr Roger Bland’s Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and another personal triumph for Gordon Heritage. Archaeologist Ros Tyrrell, 56, of the PAS, has known Heritage for many years and excavated with him at Milton Keynes. She says: “Thanks to the three finders, the coins came to me, as the local Finds Liaison Officer, well packed, with all the details of landowner and findspot. This means that the paperwork for the Coroner can be completed promptly and speeds up the treasure process. The Bucks County Council Archaeologist Service are hoping to be able to carry out a geophysical survey of the area in the hope of putting the hoard into a context. It is hoped that the finders will be involved in any further work on the site.”

Another local archaeologist, Brett Thorn of Bucks County Museum, says: “The County Museum is indeed hoping to acquire the coins, but obviously we have to wait for the treasure process to run its course, and find out what the valuation on the coins will be, before we finally decide. This is, as far as I know, the largest hoard of iron age coins found in the county since the original Whaddon hoard in 1849, and we would be very keen to have it. There is due to be an exhibition of metal detector finds (both owned by the museum, and loaned by the finders), and the work of the PAS later this year (October-January) at the museum, and if we do end up with the coins in time, I would certainly expect them to be included in that show, as one of the most impressive and important recent finds.”

Hoard of gold neckrings and bracelets, c.1150-800 BC, found with a bowl at Milton Keynes, Bucks, in 2000.

Picture source: G. Heritage.

Gordon Heritage, a 47 year old refrigeration engineer, is well named as a student of ancient history and is no stranger to defrosting Bucks’ frozen past. Indeed, he is a local heritage hero. On 7 September 2000 he and fellow detectorist Michael Rutland made history at Milton Keynes by discovering four pounds of bronze age gold jewellery – two heavy gold neckrings and three solid gold bracelets – plus a bronze age pottery bowl. Dr Stuart Needham of the British Museum said their find was of “exceptional importance” and it was valued at £290,000 by the Treasure Valuation Committee.

Dr John Sills, expert in ancient British gold coins.

Picture source: J. Sills.

Who? Why? and When?

Whaddon Chase gold staters carry no inscription. It has therefore been assumed by most scholars that their attribution to a specific person, their purpose and their date are not only unknown, but unknowable. But are they? I know of only one numismatist with the skill and the balls to tackle such a challenge: Dr John Sills of Grimsby, author of Gaulish and early British gold coinage (Spink 2003). So I asked him three questions: Who exactly issued Whaddon Chase gold staters? Why exactly? And when exactly? I believe that Dr Sills’ answers, though speculative, could prove to be a landmark in the numismatics and history of late iron age Britain. So I record them fully here for you:

Fanciful model of Cassivellaunus with the Waterloo Helmet and Battersea Shield.

Picture source: lilliput.com

Cassivellaunus, British army commander, submitting to Caesar in 54 BC.

Picture source: S. Wale, 1777.

“Whaddon Chase gold is concentrated in the area north of the Thames known to have been ruled over by Caesar’s great adversary, Cassivellaunus, in the mid 50s BC. In the late summer of 54 BC Cassivellaunus, after several pitched battles and a short guerilla war, was able to negotiate terms with Caesar that fell far short of the unconditional surrender normally demanded by the latter and allowed each side to extricate itself from a difficult situation with something of their dignity intact. Caesar, by his own admission, recognised that hostilities were by no means over, was worried about Gallic uprisings while he was on the wrong side of the Channel and knew he must return to Gaul before winter set in. So, in his own words, ‘he demanded hostages and settled the annual tribute which Britain must pay to the Roman people’. There is one, and only one, candidate to be a tribute coinage, and that is the early Whaddon Chase type.”

“Every characteristic is consistent with it being struck by Cassivellaunus in order to make annual tribute payments, and for the first time we can go beyond the written history and suggest that not only was tribute paid – for many historians have said there is no evidence it was – large shipments were probably made in 53 and 52 BC followed by a much smaller one in 51. Caesar’s last campaigns of any significance in Gaul were in 51, after which it would have become clear to the British that the threat of a third invasion had receded and they could safely stop paying.”

“Whaddon Chase staters have an almost heraldic quality, and we can see this perhaps as Cassivellaunus conveying the message to Rome that even though he had been forced to pay tribute he remained economically powerful and, in his own eyes at least, undefeated. The presence of many uniface Atrebatic staters in the Whaddon Chase hoard and the hundred of more quarter staters from Essendon, Herts, also in the territory of Cassivellaunus, hints at one of the mechanisms by which tribute may have been collected. It looks very much as if the burden was not borne solely by Cassivellaunus’ tribe, probably the Catuvellauni, but was shared between the tribes who had joined the coalition of 54 BC against Caesar, and perhaps for all we know between tribes who had refused to join as well.”

“Gold in whatever form may have been collected in by Cassivellaunus from surrounding tribes – effectively a tribute of his own – after which bullion, jewellery and coins of non-standard weight and fineness were recoined into Whaddon Chase staters. The great majority of these were then shipped across the Channel and delivered to Caesar’s armies, to join the vast quantity of gold we know he sent back to Rome.”

“But what is the Whaddon Chase hoard itself? It contains a high proportion of coins struck at or near the end of the series, and one interpretation is that it is a consignment of tribute that was not shipped for some reason. Perhaps it marks the point at which Cassivellaunus received news that Caesar was preparing to leave Gaul forever; perhaps it marks the death of the British ruler and is evidence of political or military feuding in its wake; we will probably never know.”

Bucks 1849 gold rush

This year’s hoard of Whaddon Chase gold staters is not the first to be found near Buckingham. In 1849, the year after gold was first discovered in the Sierra Nevada, California, a colossal hoard of Whaddon Chase gold staters was found at – guess where? – Whaddon Chase, near Buckingham. The first gold coins were unearthed on 14 February 1849 while a young farmhand, John Grange, was ploughing up some land owned by William Selby Lowndes of Whaddon Manor. News of the find spread fast and attracted many gold diggers who indulged in a frenzy of treasure hunting which apparently lasted four weeks. Many of the gold prospectors in this gold rush were employed by the landowner.

Four Whaddon Chase gold staters and an Atrebatic Uniface stater from the Whaddon Chase hoard, 1849.

Picture source: J. Y. Akerman, Num. Chron. XII, 1850.

In a report titled ‘California in Bucks’ the Bucks Herald (17 March 1849) said: ‘Whaddon Chase, which has long been the resort of Nimrods for hunting deer and foxes, has become the land of gold hunters.’ A Treasure Trove inquest was held on 24 March at the Haunch of Venison, Whaddon. The coroner Mr D P King ‘and a very respectable jury’, decided that Lowndes was entitled to the coins found by his labourers – ‘about 200’ coins ‘which were quite small, and of the intrinsic value of 13s each.’ However, the total number of gold coins found was much greater.

The iconography of this Whaddon Chase type stater, BMC 307, shows a radical restyling of early British gold coin-design, indicating that it is an important issue. It combines the symbolism of north and south Thames tribes, suggestive of a coalition coinage.

Picture source: Chris Rudd / CCI.

On 26 April the numismatist John Yonge Akerman told the Numismatic Society that about 320 gold coins had ‘reached the hands of Mr Lowndes’ and that nearly 100 others had been found and dispersed, making around 420 coins in all. Then, on 9 May in Aylesbury, a watchmaker, George Tooley, was charged with ‘having feloniously received 130 ancient gold coins, recently found in Whaddon Chase, knowing them to have been stolen’ and, at the court hearing, Lowndes swore that he himself ‘had received 350 of the coins’ – 150 more than the coroner had been told two months earlier – giving a new total of 480. The landowner had clearly lied at the Haunch of Venison. That’s not all.

On 16 June 316 of Lowndes’s alleged 350 gold coins were offered for sale in London by Leigh, Sotheby & Co. The catalogue stated that only 25 coins had been reserved ‘for his private cabinet’. In its report of the auction the Bucks Herald (23 June 1849) implied that a ‘larger number’ (more than 316) had already been ‘scattered about by pickers and stealers’. Dr Philip de Jersey, who is compiling a corpus of British iron age coin hoards and who kindly gave me all this information, says: “If this is an accurate reflection of the quantity of coins in circulation, rather than journalistic hyperbole, then it would suggest that at least c.640 coins were found.” Personally, I suspect that the actual total may have been three times this amount.

William Selby Lowndes, lord of Whaddon Manor. How many gold coins did his men really find?

Picture source: Google Image/Selby-Lowndes.

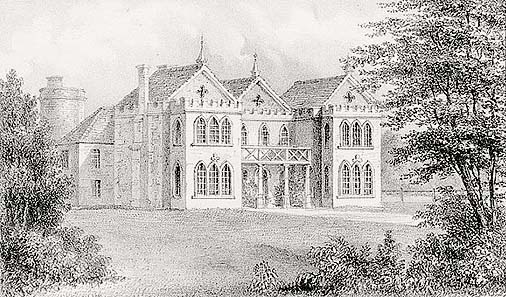

Whaddon Manor, Bucks, home of WS Lowndes.

Picture source: Google Image/Selby-Lowndes.

In The Coins of the Ancient Britons (1864, p.75) John Evans claimed that the number of gold coins found at Whaddon Chase in 1849 ‘must have been nearly 2,000, as a vast quantity found their way into the hands of some bullion dealers in London.’ Evans was a cautious numismatist, uncommonly well informed and not normally given to exaggeration. Moreover, he lived only 30 miles from Whaddon Chase and worked three or four days a week in London. So I think his claim of ‘nearly 2,000’ carries weight. Who bagged the bulk of the hoard? Local ‘pickers and stealers’ or the landowner? And who pocketed the cash from converting ‘a vast quantity’ of the coins into bullion? Local serfs, rogue traders or the lord of the manor? I leave that for you to decide.